JIBANANDA DASH

JIBANANDA DASH and his Contribution in Bengali Literature.

(Comparing with other poet)

During the later half of the twentieth century, Jibanananda Das emerged as the most popular poet of modern Bengali literature. Popularity apart, Jibanananda Das had distinguished himself as an extraordinary poet presenting a paradigm hitherto unknown. It is a fact that his unfamiliar poetic diction, choice of words and thematic preferences took time to reach the heart of the readers. Towards the later half of the twentieth century the poetry of Jibanananda has become the defining essence of modernism in twentieth century Bengali poetry.

As of 2009, Bengali is the mother tongue of more than 300 million people living mainly in Bangladesh and India. Bengali poetry of the modern age flourished on the elaborate foundation laid by Michael Madhusudan Dutt (1824–1873) and Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941). Tagore, a literary giant, without a parallel during his time, ruled over the domain of Bengali poetry and literature for more than half a century bestowing inescapable influence on contemporary poets. Bengali literature caught attention of the international literary world when Tagore was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 1913, for Gitanjali, an anthology of poems rendered into English by the poet himself with the title Song Offering. Since then Bengali poetry has traveled a long way. It has evolved around its own tradition; it has responded to the poetry movements around the world; it has assumed various dimensions in different tones, colours and essence.

In Bengal, efforts to come out of the Tagorian worldview and stylistics started in the early days of twentieth century. Poet Kazi Nazrul Islam [1899-1976] popularized himself on a wide scale with patriotic theme and musical tone and tenor. However, a number of new generation poets consciously attempted to align Bengali poetry with the essence of modernism emerging around the world, starting towards the end of the nineteenth century. Much of these can be attributed to the trends in contemporary Europe and America. Five poets who are particularly acclaimed for their contribution in creating a post-Tagorian poetic paradigm and infusing modernism in Bengali poetry are Sudhindranath Dutta [1901-1960], Buddhadeb Bose [1908-1974], Amiya Chakravarty [1901-1986], Jibanananda Das [1899-1954] and Bishnu Dey [1909-1982]. The contour of modernism in twentieth century Bengali poetry was drawn by these five pioneers and some of their contemporaries.

However, not all of them have survived the test of time. Of them, poet Jibanananda Das was little understood during his lifetime. In fact, he received scanty attention and was considered incomprehensible. Readers including his contemporary literary critics also alleged about his style and diction. On occasions, he faced merciless criticism from leading literary personalities of his time. Even Rabindranath Tagore passed unkind remarks on his diction although he praised his poetic capability. Nevertheless, destiny reserved a crown for him.

Surely, his early poems bear the influence of Kazi Nazrul Islam and some other poets like Satyendranath Dutta. However, before long, he thoroughly overcame all influences and created a new poetic diction. Buddhadeb Bose was among the few who first recognized his extraordinary style and thematic novelty. However, as his style and diction matured, his message appeared to be obscured. Readers including critics started to complain about legibility and question sensibility.

It is only after his unfortunate and accidental death in 1954 that a readership started to emerge who not only was comfortable with Jibanananda's style and diction but also enjoyed his poetry. Questions about the obscurity of his poetic message were no longer more raised. By the time his birth centenary was celebrated in 1999, Jibanananda Das was certainly the most popular and the most well-read poet of Bengali literature. Even when the last quarter of the twentieth century ushered in the post-modern era, Jibanananda Das continued to be relevant to the new taste and fervour. This has been possible because his poetry underwent many cycles of change, and later poems contain elements that precisely respond to post-modern characteristics.

Poetics

Born in 1899, Jibanananda Das started writing and publishing in the 1920s. During his lifetime he published only 269 poems in different journals and magazines of which 162 were collected in 7 anthologies, from Jhara Palak to Bela Obela Kalbela. However, since his expiry in 1954, many of his unpublished poems have been discovered and published, thanks to the dedicated initiative of his brother Asokananda Das, encouragement by his sister Sucharita Das and nephew Amitananda Das, and, above all, tireless efforts of Dr. Bhumendra Guha, who spent decades in copying from worn out published and unpublished manuscripts. By 2008, the total number of published and unpublished poems stood at more than 788. In addition, a huge number of novels and short-stories were discovered and published about the same time.

Jibanananda scholar Clinton B. Seely has termed Jibanananda Das (JD) "Bengal's most cherished poet since Rabindranath Tagore". On the other hand, to many, reading the poetry of JD is like stumbling upon a labyrinth of mind similar to the kind one imagines Camus's 'absurd' man toils through. Indeed JD's poetry is sometimes an outcome of very profound feeling that is painted with imagery of a type not readily understandable. Sometimes, the connection between the sequential lines is not obvious. In fact, JD broke the traditional circular structure of poetry (intro-middle-end) and the pattern of logical sequence of words, lines and stanzas. Consequently, the thematic connotation is often hidden under a rhythmic narrative that requires careful reading between the lines. The following excerpt will bear the point out :

Lepers open the hydrant and lap some water.

Or may be that hydrant was already broken.

Now at midnight they descend upon the city in droves.

Scattering sloshing petrol. Though ever careful,

Someone seems to have taken a serious spill in the water.

Three rickshaws trot off, fading into the last gaslight,

I turn off, leave Phear Lane, defiantly

Walk for miles, stop beside a wall

On Bentinck Street, at Territti Bazar,

There in the air dry as roasted peanuts.

(Night - a poem on night in Calcutta city, translated by Clinton B. Seely)

Variously branded at different times, and popularly known as a modernist of the Yeatsian-Poundian-Eliotesque school, JD has been termed the truest poet by Annadashankar Roy. As a true poet, JD conceived a poem and moulded it up in the most natural way. When a theme occurred to him, he shaped it up with such words, metaphors and imagery that distinguished him from all others. JD's poetry is to be felt rather than merely read or heard. Writing about JD's poetry Joe Winter remarked :

It is a natural process, though perhaps the rarest one. Jibanananda's style reminds us of this, seeming to come unbidden. It is full of sentences that scarcely pause for breath ; of word-combinations that seem altogether unlikely but work ; of switches in register, from sophisticated usage to a village-dialect word, that jar and in the same instant settle in the mind. Full of friction, in short, that almost becomes a part of the consciousness ticking.

A few lines are quoted below in support of Winter's remarks:

Nevertheless, the owl stays wide awake ;

The rotten still frog begs two more moments

in the hope of another dawn in conceivable warmth.

We feel in the deep tracelessness of flocking darkness

the unforgiving enmity of the mosquito-net all around ;

The mosquito loves the stream of life

awake in its monastery of darkness.

[One day eight years ago, translated by Faizul Latif Chowdhury]

Or elsewhere :

... how the wheel of justice is set in motion

by a smidgen of wind -

or if someone dies and someone else gives him a bottle

of medicine, free - then who has the profit? -

over all of this the four have a mighty word-battle.

For the land they will go to now is called the soaring river

where a wretched bone-picker and his bone

come and discover

their faces in water - till looking at faces is over.

(Idle Moment translated by Joe Winter)

Also noteworthy are his sonnets, the most famous of them being the seven untitled pieces collected in the publication titled "Shaat-ti Tarar Timir" (The Blackness of Seven Stars), where he describes, on one hand, his attachment to his motherland, and on the other, his views about life and death in general . They are noteworthy not only because of the picturesque description of nature that was a regular in most of his work, but also for the use of metaphors and allegories . For example, a lone owl flying about in the night sky is taken as an omen of death, while the anklets on the feet of a swan symbolizes the vivacity of life . The following are undoubtedly the most oft-quoted line from this collection :

বাংলার মুখ আমি দেখিয়াছি, তাই আমি পৃথিবীর রূপ খুঁজিতে যাই না আর...

It should be pointed out that Jibanananda successfully integrated Bengali poetry with the slightly older Euro-centric international modernist movement of early twentieth century. In this regard he possibly owes as much to his exotic exposure as to his innate poetic talent. Although hardly appreciated during his lifetime, his modernism, evoking almost all the suggested elements of the phenomenon, remains untranscended till date, despite the emergence of many notable poets during the last fifty years. His success as a modern Bengali poet may be attributed to the facts that JD in his poetry not only discovered the tract of the slowly evolving twentieth century modern mind, sensitive and reactive, full of anxiety and tension, he invented his own diction, rhythm and vocabulary with unmistakably indigenous rooting, and he maintained a self-styled lyricism and imagism mixed with an extraordinary existentialist sensuousness, perfectly suited to the modern temperament in the Indian context, whereby he also averted fatal dehumanization that could alienate him from the people. He was at once a classicist and a romantic and created an appealing world hitherto unknown :

For thousands of years I roamed the paths of this earth,

From waters round Ceylon in dead of night

to Malayan seas.

Much have I wandered. I was there

in the gray world of Asoka

And Bimbisara, pressed on through darkness

to the city of Vidarbha.

I am a weary heart surrounded by life's frothy ocean.

To me she gave a moment's peace -

Banalata Sen from Natore.

(Banalata Sen)

While reading JD, one often encounters references to olden time and places, events and personalities. Sense of time and history is an unmistakable element that has shaped JD's poetic world to a great extent. However, he lost sight of nothing surrounding him. Unlike many of his peers who blindly imitated the renowned western poets in a bid to create a new poetic domain and generated spurious poetry, JD remained anchored in his own soil and time and successfully assimilated all experiences, real and virtual, and produced hundreds of unforgettable lines. His intellectual vision was thoroughly embedded in Bengal's nature and beauty :

Amidst a vast meadow the last time when I met her

I said: 'Come again a time like this

if one day you so wish

twenty five years later.'

This been said, I came back home.

After that, many a time, the moon and the stars,

from field to field have died, the owls and the rats

searching grains in paddy fields on a moonlit night

fluttered and crept! - shut eyed

many times left and right

have slept

several souls! - awake kept I

all alone - the stars on the sky

travel fast

faster still, time speeds by.

Yet it seems

Twenty-five years will forever last.

(After Twenty-five Years translated by Luna Rushdi)

Thematically, in sum, JD is amazed by the continued existence of humankind in the backdrop of eternal flux of time, wherein individual presence is insignificant and meteoric albeit inescapable. He feels : we are closed in, fouled by the numbness of this concentration cell (Meditations). To him the world is weird and olden, and as a race, the mankind has been a persistent "wanderer of this world" (Banalata Sen) who, according to him, has existed too long to know anything more (Before death, Walking alone), or experience anything fresh. The justification of further mechanical existence like Mahin's horses (The Horses) is apparently absent. So (he) had slept by the Dhanshiri river on a cold December night, and had never thought of waking again (Darkness). As an individual, tired of life and yearning for sleep (One day eight years ago), JD is certain that peace can be found nowhere and it is useless to move to a distant land since there is no way of freedom from sorrows fixed by life (Land, Time and Offspring). Nevertheless, he suggests: "O sailor, you press on, keep pace with the sun!" (Sailor).

Why did Jibanananda task himself to forge a new poetic speech while others in his time preferred to tread the usual path? The answer is simple. In his endeavours to shape a world of his own, he was gradual and steady. He was an inward looking person and was not in a hurry.

I do not want to go anywhere so fast.

Whatever my life wants I have time to reach

there walking

[Of 1934 - a poem on Motor Car, translated by Golam Mustafa].

Bibhav, in Poet's birth centenary, published his 40 poems, that were yet unpublished. Shamik Bose has translated one poem, untiltled as it was by the Poet. Here is the Bengali original by the Poet.

ঘুমায়ে পড়িতে হবে একদিন আকাশের নক্ষত্রের তলে

শ্রান্ত হয়ে-- উত্তর মেরুর সাদা তুষারের সিন্ধুর মতন!

এই রাত্রি,--- এই দিন,--- এই আলো,--- জীবনের এই আয়োজন,---

আকাশের নিচে এসে ভুলে যাব ইহাদের আমরা সকলে!

একদিন শরীরের স্বাদ আমি জানিয়াছি, সাগরের জলে

দেহ ধুয়ে;--- ভালোবেসে ভিজইয়েছি আমাদের হৃদয় কেমন!

একদিন জেগে থেকে দেখিয়েছি আমাদের জীবনের এই আলোড়ন,

আঁধারের কানে আলো--- রাত্রি দিনের কানে কানে কত কথা বলে

শুনিয়াছি;--- এই দেখা--- জেগে থাকা একদিন তবু সাংগ হবে,---

মাঠের শস্যের মত আমাদের ফলিবার রহিয়াছে সময়;

একবার ফলে গেলে তারপর ভাল লাগে মরণের হাত,---

ঘুমন্তের মত করে আমাদের কখন সে বুকে তুলে লবে!---

সেই মৃত্যু কাছে এসে একে একে সকলেরে বুকে তুলে লয়;---

সময় ফুরায়ে গেলে সব চেয়ে ভাল লাগে তাহার আস্বাদ!---

Here is a translation in English by Shamik Bose.

Under this sky, these stars' beneath --

One day will have to sleep inside tiredness ---

Like snow-filled white ocean of North Pole! ---

This night - this day - O this light as bright as it may! --

These designs for a life - will forget all --

Under such a silent fathomless sky! --

Had felt the fragrance of a body one day, --

By washing my body inside sea water --

Felt our heart so deep by falling in love! --

This vigor of life- had seen one day awaken --

Light stoking the edge of darkness --

Have heard the passionate whispers of a night - always for a day! --

This visit! This conscious vigil that I see, I feel --

Yet will end one day --

Time only remain for us to ripe like a harvest in green soil --

Once so ripen, then the hands of death will be likeable--

Will hold us in his chest, one by one --

Like a sleeplorn --

Fugitive lovelorn --

Inside tender whispers! --

When that time will prosper to an end and he will come --

That savor will be .. the most relishing.

Notwithstanding indigenous anchorage and very own world-view, stylistics and diction, Jibanananda Das will appeal to poetry lovers and modern men of intellect and emotion all around the world of today and of tomorrow.

A huge volume of literary evaluation of the poetry of Jibanananda Das has been produced since his untimely death in 1954. However, English language readers will immensely benefit from the 10-page Introduction of "Naked Lonely Hand", an anthology of poet's fifty poems into English, written by Joe Winter. Winter has been able to successfully catch the essence of the poet who appeared to be subtle, mysterious and bizarre even to native readers and critics of his time. He is also known as a surrealist poet for his spontaneous overflow of subconscious mind in his poetry and especially in diction. Subconscious mind takes hold on the poet when he is creative frenzy.

Biographical account

Source: Seely, Clinton (1990) A Poet Apart: a literary biography of the Bengali Poet Jibanananda Das. Newark, Del: University of Delaware Press

Early life

Jibanananda Das (JD) was born in 1899 in the small district town of Barisal, located in the south of Bangladesh. His ancestors came from the Bikrampur region of Dhaka district, from a now-extinct village called Gaupara on the banks of the river Padma. Jibanananda's grandfather Sarbananda Dasgupta was the first to settle permanently in Barisal. He was an early exponent of the reformist Brahmo Samaj movement in Barisal, and was highly regarded in town for his philanthropy. He erased the -gupta suffix from the family name as a symbol of Vedic Brahmin excess, thus rendering the surname to Das. Jibanananda's father Satyananda Das (1863–1942) was a schoolmaster, essayist, magazine publisher, and founder-editor of Brôhmobadi, a journal of the Brahmo Samaj dedicated to the exploration of various social issues.

Jibanananda's mother Kusumkumari Das was a poet and the writer of a famous poem called 'Adôrsho Chhele' (The Ideal Boy) whose refrain is well known to Bengalis to this day: Amader deshey hobey shei chhele kobey / Kothae na boro hoye kajey boro hobey. (The child who achieves not in words but in deeds, when will this land know such a one?)

Jibanananda was the eldest son of his parents, and was called by the nickname Milu. A younger brother Ashokananda Das was born in 1908 and a sister called Shuchorita in 1915. Milu fell violently ill in his childhood, and his parents feared for his life. Kusumkumari took her ailing child and travelled to health resorts all over India, Lucknow, Agra and Giridih. They were accompanied on these journeys by their uncle Chandranath.

In January 1908, Milu, by now eight years old, was admitted to the fifth grade in Brojomohon School. The delay was due to his father's opposition to admitting children into school at too early an age. Milu's childhood education was therefore sustained mostly at home, under his mother's tutelage.

His school life passed by relatively uneventfully. In 1915, he successfully completed his Matriculation examination from Brojomohon, obtaining a first division in the process. He repeated the feat two years later when he passed the Intermediate exams from Brajamohan College. Evidently an accomplished student, he left his rural Barisal to join the University of Calcutta.

Life in Calcutta: first phase

Jibanananda enrolled in Presidency College, Kolkata, then as now one of the most prestigious seats of learning in India. He studied English Literature and graduated with a BA (Honours) degree in 1919. That same year, his first poem appeared in print in the Boishakh issue of Brahmobadi journal. Fittingly, the poem was called Borsho-abahon (Arrival of the New Year). This poem was published anonymously, with only the honorific Sri in the byline. However, the annual index in the year-end issue of the magazine revealed his full name: "Sri Jibanananda Das Gupta, BA".

In 1921, he completed the MA degree in English from University of Calcutta, obtaining a second class. He was also studying law. At this time, he lived in the Hardinge student quarters next to the university. Just before his exams, he fell ill with bacillary dysentery that affected his preparation for the examinaiton.

The following year, he started his teaching career. He joined the English department of City College, Calcutta as a tutor. By this time, he had left Hardinge and moved to boardings in Harrison Road. He gave up his law studies. It is thought that he also lived in a house in Bechu Chatterjee Street for some time with his brother Ashokanananda who had come up from Barisal for his MSc studies.

Travels and travails

His literary career was starting to take off. When Deshbondhu Chittaranjan Das died in June 1925, Jibanananda wrote a poem called 'Deshbandhu'r Prayan'e' (On the Death of the Friend of the Nation') which was published in Bangabani magazine. This poem would later take its place in the collection called Jhara Palok (1927). On reading it, poet Kalidas Roy said that he had thought the poem was the work of a mature, accomplished poet hiding behind a pseudonym. Jibanananda's earliest printed prose work was also published in 1925. This was an obituary entitled 'Kalimohan Das'er Sraddha-bashorey', which appeared in serialized form in Brahmobadi magazine. His poetry began to be widely published in various literary journals and little magazines in Calcutta, Dhaka and elsewhere. These included Kallol, perhaps the most famous literary magazine of the era, Kalikalam (Pen and Ink), Progoti (Progress) (co-edited by Buddhadeb Bose) and others. At this time, he occasionally used the surname Dasgupta as opposed to Das.

In 1927, Jhara Palok (Fallen Feathers), his first collection of poems, came out. A few months later, Jibanananda was fired from his job at the City College. The college had been struck by student unrest surrounding a religious festival, and enrolment seriously suffered as a consequence. Still in his late 20s, Jibanananda was the youngest member of the faculty and therefore the most dispensable. In the literary circle of Calcutta, he also came under serial attack. One of the most serious literary critic of that time Sajanikanta Das began to write aggressive critiques of his poetry in the review pages of Shanibarer Chithi (The Saturday Letter) magazine.

With nothing to keep him in Calcutta, Jibanananda left for the small town of Bagerhat in the far south, there to resume his teaching career at the Prafulla Chandra College. But only after about three months he returned to the big city. He was now in dire financial straits. In order to make both the ends meet, he gave private tuition to students while applying for full-time positions in academia. In December 1929, he moved to Delhi to take up a teaching post at the Ramjosh College. But again this lasted no more than a few months. Back in Barisal, his family had been making arrangements for his marriage. Once Jibanananda got to Barisal, he failed to go back to Delhi and consequently lost the job.

In May 1930, he married Labanya, a girl whose ancestors came from Khulna. At the subsequent reception in Dhaka's Ram Mohan Library, leading literary lights of the day such as Ajit Kumar Dutta and Buddhadeb Bose were assembled. A daughter called Manjusree was born to the couple in February of the following year.

Around this time, he wrote one of his most controversial poems. 'Camp'e' (At the Camp) was printed in Sudhindranath Dutta's Parichay magazine and immediately caused a firestorm in the literary circle of Calcutta. The poem's ostensible subject is a deer hunt on a moonlit night. Many accused Jibanananda of promoting indecency and incest through this poem.More and more, he turned now, in secrecy, to fiction. He wrote a number of short novels and short stories during this period of unemployment, strife and utter frustration.

In 1934, he wrote the series of poems that would form the basis of the collection called Rupasi Bangla. These poems were not discovered during his lifetime and Rupasi Bangla was only published in 1957, three years after his death.

Back in Barisal

In 1935, Jibanananda, by now familiar with professional disappointment and poverty, returned to his alma mater Brajamohan College, which was then affiliated with the University of Calcutta. He joined as a lecturer in the English department. In Calcutta, Buddhadeb Bose, Premendra Mitra and Samar Sen were starting a brand new poetry magazine called Kobita. Jibanananda's work featured in the very first issue of the magazine, a poem called Mrittu'r Aagey (Before Death). Upon reading the magazine, Tagore wrote a lengthy letter to Bose and especially commended the Das poem: Jibanananda Das' vivid, colourful poem has given me great pleasure. It was in the second issue of Kobita (Poush 1342 issue, Dec 1934/Jan 1935) that Jibanananda published his now-legendary Banalata Sen. Today, this 18-line poem is among the most famous poems in the language.

The following year, his second volume of poetry Dhusar Pandulipi was published. Jibanananda was by now well settled in Barisal. A son Samarananda was born in November 1936. His impact in the world of Bengali literature continued to increase. In 1938, Tagore compiled a poetry anthology entitled Bangla Kabya Parichay (Introduction to Bengali Poetry) and included an abridged version of Mrityu'r Aagey, the same poem that had moved him three years ago. Another important anthology came out in 1939, edited by Abu Sayeed Ayub and Hirendranath Mukhopadhyay; Jibanananda was represented with four poems: Pakhira, Shakun, Banalata Sen, and Nagna Nirjan Haat.

In 1942, the same year that his father died, his third volume of poetry Banalata Sen was published under the aegis of Kobita Bhavan and Buddhadeb Bose. A ground-breaking modernist poet in his own right, Bose was a steadfast champion of Jibanananda's poetry, providing him with numerous platforms for publication. 1944 saw the publication of Maha Prithibi. The Second World War had a profound impact on Jibanananda's poetic vision. The following year, Jibanananda provided his own translations of several of his poems for an English anthology to be published under the title Modern Bengali Poems. Oddly enough, the editor Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya considered these translations to be sub-standard, and instead commissioned Martin Kirkman to translate four of Jibanananda's poems for the book. Life in Calcutta: final phase

The aftermath of the war saw heightened demands for Indian independence. Muslim politicians led by Jinnah wanted an independent homeland for the Muslims of the subcontinent. Bengal was uniquely vulnerable to partition: its western half was majority-Hindu, its eastern half majority-Muslim. Yet adherents of both religions spoke the same language, came from the same ethnic stock, and lived in close proximity to each other in town and village. Jibanananda had emphasized the need for communal harmony at an early stage. In his very first book Jhora Palok, he had included a poem called Hindu Musalman. In it he proclaimed:

However, events in real life belied his beliefs. In the summer of 1946, he travelled to Calcutta from Barisal on three months' paid leave. He stayed at his brother Ashokananda's place through the bloody riots that swept the city. Just before partition in August 1947, Jibanananda quit his job at Brajamohan College and said goodbye to his beloved Barisal. He and his family were among the X million refugees who took part in the largest cross-border exchange of peoples in history. For a while he worked for a magazine called Swaraj as its Sunday editor. But he left the job after a few months.

In 1948, he completed two of his novels, Mallyaban and Shutirtho, neither of which were discovered during his life. Shaat'ti Tarar Timir was published in December 1948. The same month, his mother Kusumkumari Das died in Calcutta.

By now, he was well established in the Calcutta literary world. He was appointed to the editorial board of yet another new literary magazine Dondo (Conflict). However, in a reprise of his early career, he was sacked from his job at Kharagpur College in February 1951. In 1952, Signet Press published Banalata Sen. The book received widespread acclaim and won the Book of the Year award from the All-Bengal Tagore Literary Conference. Later that year, the poet found another job at Borisha College (today known as Borisha Bibekanondo College). This job too he lost within a few months. He applied afresh to Diamond Harbour Fakirchand College, but eventually declined it, owing to travel difficulties. Instead he was obliged to take up a post at Howrah Girl's College (now known as Bijoy Krishna Girls’ College), a constituent affiliated undergraduate college of the University of Calcutta. As the head of the English department, he was entitled to a 50-taka monthly bonus on top of his salary.

By the last year of his life, Jibanananda was acclaimed as one of the best poets of the post-Tagore era. He was constantly in demand at literary conferences, poetry readings, radio recitals etc. In May 1954, he was published a volume titled 'Best Poems' (Sreshttho Kobita). His Best Poems won the Indian Sahitya Akademi Award in 1955.

Love and marriage

Young Jibanananda fell in love with Shovona, daughter of his uncle Atulchandra Das, who lived in the neighbourhood. He dedicated his first anthology of poems to Shovona without mentioning her name explicitly. He did not try to marry Shovona since marriage between cousins was not approvable by the society. But he never forgot Shovona who went by her nick Baby. She has been referred to as Y in his literary notes. Soon after wedding with Labanyaprabha Das (née Gupta) in 1930, personality clash erupted and Jibanananda Das gave up hope of a happy married life. The gap with his wife never narrowed. While Jibanananda was struggling with death after a tram accident on 14 October 1954, Labanyaprabha did not find time for more than once for visiting her husband on death bed. At that time she was busy in film-making in Tollyganj.

[] Death

On October 14, 1954, he was carelessly crossing a road near Calcutta's Deshapriya Park when he was hit by a tram. Jibanananda was returning home after his routine evening walk. At that time, he used to reside in a rented apartment on the Lansdowne Road. Seriously injured, he was taken to Shambhunath Pundit Hospital. Poet-writer Sajanikanta Das who had been one of his fiercest critics was tireless in his efforts to secure the best treatment for the poet. He even persuaded Dr. Bidhan Chandra Roy (then chief minister of West Bengal) to visit him in hospital. Nonetheless, the injury was too severe to redress. Jibanananda died in hospital on October 22, 1954 eight days later, at about midnight. He was then 55 and left behind his wife, Labanyaprabha Das, a son and a daughter, and the ever-growing band of readers.

His body was cremated the following day at Keoratola crematorium. Following popular belief, it has been alleged in some biographical accounts that his accident was actually an attempt at suicide.Although none of the Jibanananda biographers have indicated such, it appears from circumstantial evidence that it was an attempt to end his own life.

The literary circle deeply mourned his death. Almost all the newspapers published obituaries which contained sincere appreciations of the poetry of Jibanananda. Poet Sanjay Bhattacharya wrote the death news and sent to different newspapers. On 1 November 1954, The Times of India wrote :

The premature death after an accident of Mr. Jibanananda Das removes from the field of Bengali literature a poet, who, though never in the limelight of publicity and prosperity, made a significant contribution to modern Bengali poetry by his prose-poems and free-verse. ... A poet of nature with a serious awareness of the life around him Jibanananda Das was known not so much for the social content of his poetry as for his bold imagination and the concreteness of his image. To a literary world dazzled by Tagore’s glory, Das showed how to remain true to the poet’s vocation without basking in its reflection.”

In his obituary in the Shanibarer Chithi, Sajanikanta Das quoted from the poet :

When one day I’ll leave this body once for all −

Shall I never return to this world any more?

Let me come back

On a winter night

To the bedside of any dying acquaintance

With a cold pale lump of orange in hand.

Everyday Jibanananda returns to thousand of his readers and touches them with his unforgettable lines.

Prose style

During his lifetime Jibanananda remained solely a poet who occasionally wrote literary articles, mostly on request. Only after his death were a huge number of novels and short-stories discovered. Thematically, Jibanananda's storylines are largely autobiographical. His own time constitutes the perspective. While in poetry he subdued his own life, he allowed it to be brought into his fiction. Structurally his fictional works are based more on dialogues than description by the author. However, his prose shows a unique style of compound sentences, use of non-colloquial words and a typical pattern of punctuation. His essays evidence a heavy prose style, which although complex, is capable of expressing complicated analytical statements. As a result his prose was very compact, containing profound messages in a relatively short space.

Major works

Poetry

Jhôra Palok (Fallen Feathers), 1927.

Dhushor Pandulipi (Grey Manuscript), 1936.

Bônolôta Sen, 1942

Môhaprithibi (Great Universe), 1944 :

Shaat-ti Tarar Timir, (Darkness of Seven Stars), 1948.

Shreshtho Kobita, (Best Poems),1954 : Navana, Calcutta, .

Rupôshi Bangla (Bengal, the Beautiful), written in 1934, published posthumously in 1957.

Bela Obela Kalbela (Times, Bad Times, End Times), 1961, published posthumously but the manuscript was prepared during lifetime.

Sudorshona(The beautiful), published posthumously in 1973: Sahitya Sadan, Calcutta.

Alo Prithibi (The World of Light), published posthumously in 1981 :Granthalaya Private Ltd., Calcutta.

Manobihangam (The Bird that is my Heart), published posthumously in 1979 : Bengal Publishers Private Ltd. Calcutta.

Oprkashitô Ekanno (Unpublished Fifty-one), Published posthumously in 1999, Mawla Brothers, Dhaka.

Novels

Malyabaan (novel), New Script, Calcutta, 1973 (posthumuously published).

Purnima

Kalyani

Chaarjon

Bibhav

Mrinal

Nirupam Yatra

Karu-Bashona

Jiban-Pronali

Biraaj

Pretinir

Sutirtha

Bashmatir Upakhyan

Short stories

Akankha-Kamonar Bilas

Sango, Nisongo

Raktomangsohin

Nirupam Jatra

Jamrultola

Paliye Jete

Meyemnus

Hiseb-nikes

Kotha sudhu Kotha, Kotha, Kotha

Purnima

Kuashar Vitor Mrityur Somoy

Meyemanuser Ghrane

Mangser Kanti

Bibahito Jibon

Nakoler Khelae

Ma hoyar kono Saadh

Premik Swami

Mohisher Shingh

Basor Sojyar pase

Taajer Chobi

Sari

Hater Tas

Chakri Nei

Aekgheye Jibon

Kinnorlok

Sheetrater Andhokare

Prithibita Sishuder Noy

Jadur Desh

Chayanot

Somnath o Shrimoti

Bilas

Upekkhar Sheet

Boi

Sadharon Manus

Britter moto

Non-fiction

Kobitaar Kôtha (tr. On Poetry), Signet Press, Calcutta, 1362 (Bengali year).

Rabindranath o Adhunik Bangla Kobita

Matrachetona

Uttoroibik Banglakabbyo

Kobita Prosonge

Kobitar Atma o Sorir

Ki hisebe Saswato

Kobitapath

Desh kal o kobita

Sottyo Biswas o Kobita

Ruchi, Bichar o Onnanyo kotha

Kobitar Alochona

Adhunik Kobita

Bangla Kobitar Bhobishyot

Asomapto Alochona

Lekhar Kotha

Kobita o Konkaboti

Sikkha, Dikkha Sikkhokota

Sikkhar Kotha

Sikkha-Dikkha

Sikkha o Ingrezi

Ektukhani

Amar Baba

Amar Ma

Rasoranjan Sen

Prithibi o Somoy

Sottendranath Dutt

Nazrul Islam

"Aat Bachor Ager Din" prosonge

"Dhusor Pandulipi" prosonge

Ekti Aprokashito Kobita

Jukti Jiggasha o Bangali

Bangla Bhasa o Sahittyer Bhobshiyot

Swapno kamona'r bhumika

Keno Likhi

Sworgiyo Kalimohon Daser sradhobasore

Saratchandra

"Camp"-e

English essays

The Bengali novel today

The Bengali Poetry today

Konkaboti: Buddhadeb Basu

Aongikar: Krishna Dhar

Sheete Upekkhita: Ranjan

Journal: Gide

Gioconda Smile: Aldous Huxley

Three Voices of Poetry: T. S. Eliot

Doctor Faustus: Thomas Mann

Major Collected Texts

Bandopdhaya, Deviprasad : Kabya Songroho − Jibanananda Das (tr. Collection of Poetry of Jibanananda Das), 1993, Bharbi, 13/1 Bankim Chatterjje Street, Kolkata-73.

Bandopdhaya, Deviprasad : Kabya Songroho − Jibanananda Das (tr. Collection of Poetry of Jibanananda Das), 1999, Gatidhara, 38/2-KA Bangla Bazaar, Dhaka-1100, Bangladesh.

Bandopdhaya, Deviprasad : Jibanananda Das Uttorparba (1954–1965), 2000, Pustak Bipani, Calcutta.

Chowdhury, Faizul Latif (editor) (1990), Jibanananda Das'er Prôbôndha Sômôgrô, (tr: Complete non-ficitonal prose works of Jibanananda Das), First edition : Desh Prokashon, Dhaka.

Chowdhury, Faizul Latif (editor) (1995), Jibanananda Das'er Prôbôndha Sômôgrô, (tr: Complete non-ficitonal prose works of Jibanananda Das), Second edition : Mawla Brothers, Dhaka.

Chowdhury, F. L. (ed) : Oprokashito 51 (tr. Unpublished fifty one poems of Jibanananda Das), 1999, Mawla Brothers, Dhaka.

Shahriar, Abu Hasan : Jibanananda Das-er Gronthito-Ogronthito Kabita Samagra, 2004, Agaami Prokashoni, Dhaka.

Jibanananda in English Translation

Translating Jibanananda Das (JD) poses a real challenge to any translator. It not only requires translation of words and phrases, it demands 'translation' of colour and music, of imagination and images. Translations are a works of interpretation and reconstruction. When it comes to JD, both are quite difficult.

However people have shown enormous enthusiasm in translating JD. Translation of JD commenced as the poet himself rendered some of his poetry into English at the request of poet Buddhadeb Bose for the Kavita. That was 1952. His translations include Banalata Sen, Meditations, Darkness, Cat and Sailor among others, many of which are now lost. Since then many JD lovers have taken interest in translating JD's poetry into English. These have been published, home and abroad, in different anthologies and magazines.

Obviously different translators have approached their task from different perspectives. Some intended to merely transliterate the poem while others wanted to maintain the characteristic tone of Jibanananda as much as possible. As indicated above, the latter is not an easy task. In this connection, it is interesting to quote Chidananda Dasgupta who informed of his experience in translating JD :

JIBONANDA DAS in Wikipedia (English)

JIBONANDA DAS in Wikipedia (Bengali)

Kazi Nazrul Islam

Early life

Nazrul in the Army

Kazi Nazrul Islam was born in the village of Churulia near Asansol in the Burdwan District of Bengal (now located in the Indian state of West Bengal). He was born in a powerful Muslim Taluqdar family and was the second of three sons and a daughter, Nazrul's father Kazi Faqeer Ahmed was the imam and caretaker of the local mosque and mausoleum. Nazrul's mother was Zahida Khatun. Nazrul had two brothers, Kazi Saahibjaan and Kazi Ali Hussain, and a sister, Umme Kulsum. Nicknamed Dukhu Mian (Sad Man), Nazrul began attending the maktab & madarsa ; the local religious school run by the mosque & dargah where he studied the Qur'an and other scriptures, Islamic philosophy and theology. His family was devastated with the death of his father in 1908. At the young age of ten, Nazrul began working in his father's place as a caretaker to support his family, as well as assisting teachers in school. He later became the muezzin at the mosque, delivering the Azaan and calling the people for prayer.

Attracted to folk theatre, Nazrul joined a leto (travelling theatrical group) run by his uncle Fazl e Karim. Working and travelling with them, learning acting, as well as writing songs and poems for the plays and musicals. Through his work and experiences, Nazrul began learning Bengali and Sanskrit literature, as well as Hindu scriptures such as the Puranas. The young poet composed a number of folk plays for his group, which included "Chashaar Shong" ("The drama of a peasant"), "Shakunibadh" ("The Killing of Shakuni a character from the epic Mahabharata"), "Raja Yudhisthirer Shong" ("The drama of King Yudhisthira again from the Mahabharata"), "Daata Karna" ("Philanthropic Karna from the Mahabharata"), "Akbar Badshah" ("Emperor Akbar"), "Kavi Kalidas" ("Poet Kalidas"), "Vidyan hutum" ("The Learned Owl"), and "Rajputrer Shong" ("The drama of a Prince"),

In 1910, Nazrul left the troupe and enrolled at the Searsole Raj High School in Raniganj (where he came under influence of teacher, revolutionary and Jugantar activist Nibaran Chandra Ghatak, and initiated life-long friendship with fellow author Sailajananda Mukhopadhyay, who was his classmate), and later transferred to the Mathrun High English School, studying under the headmaster and poet Kumudranjan Mallik. Unable to continue paying his school fees, Nazrul left the school and joined a group of kaviyals. Later he took jobs as a cook at the house of a Christian railway guard and at the most famous bakery of the region Wahid's/Abdul Wahid and tea stall in the town of Asansol. In 1914, Nazrul studied in the Darirampur School (now Jatiya Kabi Kazi Nazrul Islam University) in Trishal, Mymensingh District. Amongst other subjects, Nazrul studied Bengali, Sanskrit, Arabic, Persian literature and classical music under teachers who were impressed by his dedication and skill.

Studying up to Class X, Nazrul did not appear for the matriculation pre-test examination, enlisting instead in the Indian Army in 1917 at the age of eighteen. He joined the British army mainly for two reasons: first, his youthful romantic inclination to respond to the unknown and, secondly, the call of politics. Attached to the 49th Bengal Regiment, he was posted to the cantonment in Karachi, where he wrote his first prose and poetry. Although he never saw active fighting, he rose in rank from corporal to havildar, and served as quartermaster for his battalion. During this period, Nazrul read extensively, and was deeply influenced by Rabindranath Tagore and Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, as well as the Persian poets Hafez, Rumi and Omar Khayyam. He learnt Persian poetry from the regiment's Punjabi moulvi, practiced music and pursued his literary interests. His first prose work, "Baunduler Atmakahini" ("Life of a Vagabond") was published in May, 1919. His poem "Mukti" ("Freedom") was published by the "Bangla Mussalman Sahitya Patrika" ("Bengali Muslim Literary Journal") in July 1919.

Rebel poet

Young Nazrul

Nazrul left the army in 1920 and settled in Calcutta, which was then the "cultural capital" of India (it had ceased to be the political capital in 1911). He joined the staff of the “Bangiya Mussalman Sahitya Samiti” ("Bengali Muslim Literary Society") and roomed at 32 College Street with colleagues. He published his first novel "Bandhan-hara" ("Freedom from bondage") in 1920, which he kept working on over the next seven years. His first collection of poems included "Bodhan", "Shat-il-Arab", "Kheya-parer Tarani" and "Badal Prater Sharab" and received critical acclaim.

Working at the literary society, Nazrul grew close to other young Muslim writers including Mohammad Mozammel Haq, Afzalul Haq, Kazi Abdul Wadud and Muhammad Shahidullah. He was a regular at clubs for Calcutta's writers, poets and intellectuals like the Gajendar Adda and the Bharatiya Adda. In October 1921, Nazrul went to Santiniketan with Muhammad Shahidullah and met Rabindranath Tagore. Despite many differences, Nazrul looked to Tagore as a mentor and the two remained in close association. In 1921, Nazrul was engaged to be married to Nargis, the niece of a well-known Muslim publisher Ali Akbar Khan, in Daulatpur, Comilla. But on June 18, 1921—the day of the wedding—upon public insistence by Ali Akbar Khan that the term "Nazrul must reside in Daulatpur after marriage" be included in the marriage contract, Nazrul walked away from the ceremony.Nazrul reached the peak of fame with the publication of "Bidrohi" in 1922, which remains his most famous work, winning admiration of India's literary classes by his description of the rebel whose impact is fierce and ruthless even as its spirit is deep:.

I am the unutterable grief,

I am the trembling first touch of the virgin,

I am the throbbing tenderness of her first stolen kiss.

I am the fleeting glance of the veiled beloved,

I am her constant surreptitious gaze...

...

I am the burning volcano in the bosom of the earth,

I am the wild fire of the woods,

I am Hell's mad terrific sea of wrath!

I ride on the wings of lightning with joy and profundity,

I scatter misery and fear all around,

I bring earth-quakes on this world! “(8th stanza)” I am the rebel eternal,

I raise my head beyond this world,

High, ever erect and alone! “(Last stanza)” (English translation by Kabir Choudhary)

Published in the "Bijli" (Thunder) magazine, the rebellious language and theme was popularly received, coinciding with the Non-cooperation movement — the first, mass nationalist campaign of civil disobedience against British rule.

Nazrul explores a synthesis of differ forces in a rebel, destroyer and preserver, expressing rage as well as beauty and sensitivity. Nazrul followed up by writing "Pralayollas" ("Destructive Euphoria"), and his first anthology of poems, the "Agniveena" ("Lyre of Fire") in 1922, which enjoyed astounding and far-reaching success. He also published his first volume of short stories, the "Byather Dan" ("Gift of Sorrow") and "Yugbani", an anthology of essays.

Revolutionary

Nazrul with his first son Bulbul; his wife Pramila seated right and his mother-in-law Giribala Devi seated left, behind whom stands Bulbul's nanny

Nazrul started a bi-weekly magazine, publishing the first "Dhumketu" (Comet) on August 12, 1922. Earning the moniker of the "rebel poet”, Nazrul also aroused the suspicion of British authorities. A political poem published in "Dhumketu" in September 1922 led to a police raid on the magazine's office. Arrested, Nazrul entered a lengthy plea before the judge in the court.

I have been accused of sedition. That is why I am now confined in the prison. On the one side is the crown, on the other the flames of the comet. One is the king, sceptre in hand; the other Truth worth the mace of justice. To plead for me, the king of all kings, the judge of all judges, the eternal truth the living God... His laws emerged out of the realization of a universal truth about mankind. They are for and by a sovereign God. The king is supported by an infinitesimal creature; I by its eternal and indivisible Creator. I am a poet; I have been sent by God to express the unexpressed, to portray the unportrayed. It is God who is heard through the voice of the poet... My voice is but a medium for Truth, the message of God... I am the instrument of that eternal self-evident truth, an instrument that voices forth the message of the ever-true. I am an instrument of God. The instrument is not unbreakable, but who is there to break God?

On April 14, 1923 he was transferred from the jail in Alipore to Hooghly in Kolkata, he began a 40-day fast to protest mistreatment by the British jail superintendent. Nazrul broke his fast more than a month later and was eventually released from prison in December 1923. Nazrul composed a large number of poems and songs during the period of imprisonment and many his works were banned in the 1920s by the British authorities.

Kazi Nazrul Islam became a critic of the Khilafat struggle, condemning it as hollow, religious fundamentalism. Nazrul's rebellious expression extended to rigid orthodoxy in the name of religion and politics. Nazrul also criticised the Indian National Congress for not embracing outright political independence from the British Empire. He became active in encouraging people to agitate against British rule, and joined the Bengal state unit of the Congress party. Nazrul also helped organise the Sramik Praja Swaraj Dal, a political party committed to national independence and the service of the peasant masses. On December 16, 1925 Nazrul started publishing the weekly "Langal”, with himself as chief editor. The "Langal" was the mouthpiece of the Sramik Praja Swaraj Dal.

During his visit to Comilla in 1921, Nazrul met a young Hindu woman, Pramila Devi, with whom he fell in love and they married on April 25, 1924. Pramila belonged to the Brahmo Samaj, which criticised her marriage to a Muslim. Nazrul in turn was condemned by Muslim religious leaders and continued to face criticism for his personal life and professional works, which attacked social and religious dogma and intolerance. Despite controversy, Nazrul's popularity and reputation as the "rebel poet" rose significantly.

Weary of struggles, I, the great rebel,

Shall rest in quiet only when I find

The sky and the air free of the piteous groans of the oppressed. Only when the battle fields are cleared of jingling bloody sabres

Shall I, weary of struggles, rest in quiet,

I the great rebel.

Mass music

Nazrul on a hunting trip with friends in Sundarpur India

With his wife and young son Bulbul, Nazrul settled in Krishnanagar in 1926. His work began to transform as he wrote poetry and songs that articulated the aspirations of the downtrodden classes, a sphere of his work known as "mass music." Nazrul assailed the socio-economic norms and political system that had brought upon misery. From his poem 'Daridro' Bengali: দারিদ্র (poverty or pain):

O poverty, thou hast made me great.

Thou hast made me honoured like Christ

With his crown of thorns. Thou hast given me

Courage to reveal all. To thee I owe

My insolent, naked eyes and sharp tongue.

Thy curse has turned my violin to a sword...

O proud saint, thy terrible fire

Has rendered my heaven barren.

O my child, my darling one

I could not give thee even a drop of milk

No right have I to rejoice.

Poverty weeps within my doors forever

As my spouse and my child.

Who will play the flute?

Kazi Nazrul Islam

In what his contemporaries regarded as one of his greatest flairs of creativity, Nazrul began composing the very first ghazals in Bengali, transforming a form of poetry written mainly in Persian and Urdu. Nazrul became the first person to introduce Islam into the larger mainstream tradition of Bengali music. The first record of Islamic songs by Nazrul Islam was a commercial success and many gramophone companies showed interest in producing these. A significant impact of Nazrul was that it drew made Muslims more comfortable in the Bengali Arts, which used to be dominated by Hindus. Nazrul also composed a number of notable Shamasangeet, Bhajan and Kirtan, combining Hindu devotional music. Arousing controversy and passions in his readers, Nazrul's ideas attained great popularity across India. In 1928, Nazrul began working as a lyricist, composer and music director for His Master's Voice Gramophone Company. The songs written and music composed by him were broadcast on radio stations across the country. He was also enlisted/attached with the Indian Broadcasting Company.

Nazrul professed faith in the belief in the equality of women — a view his contemporaries considered revolutionary. From his poet Nari (Woman)

I don't see any difference

Between a man and woman

Whatever great or benevolent achievements

That are in this world

Half of that was by woman,

The other half by man. (Translated by Sajed Kamal)

His poetry retains long-standing notions of men and women in binary opposition to one another and does not affirm gender similarities and flexibility in the social structure:

Man has brought the burning, scorching heat of the sunny day;

Woman has brought peaceful night, soothing breeze and cloud.

Man comes with desert-thirst; woman provides the drink of honey.

Man ploughs the fertile land; woman sows crops in it turning it green.

Man ploughs, woman waters; that earth and water mixed together, brings about a harvest of golden paddy.

However, Nazrul's poems strongly emphasise the confluence of the roles of both sexes and their equal importance to life. He stunned society with his poem "Barangana" ("Prostitute"), in which he addresses a prostitute as "mother". Nazrul accepts the prostitute as a human being, reasoning that this person was breast-fed by a noble woman and belonging to the race of "mothers and sisters"; he assails society's negative notions of prostitutes.

Who calls you a prostitute, mother?

Who spits at you?

Perhaps you were suckled by someone

as chaste as Seeta.

...

And if the son of an unchaste mother is 'illegitimate',

so is the son of an unchaste father.

("Barangana" ("Prostitute") Translated by Sajed Kamal)

Nazrul was an advocate of the emancipation of women; both traditional and non-traditional women were portrayed by him with utmost sincerity. Nazrul's songs are collectively called as Nazrul geeti.

Exploring religion

Kazi Nazrul Islam

Nazrul's mother died in 1928, and his second son Bulbul died of smallpox the following year. His first son, Krishna Mohammad had died prematurely. His wife gave birth to two more sons — Savyasachi in 1928 and Aniruddha in 1931 — but Nazrul remained shaken and aggrieved for a long time.

Come back my birdie! Come back again to my empty bosom! Shunno e bookey paakhi mor aaye! Phirey aaye phirey aaye!

His works changed significantly from rebellious expositions of society to deeper examination of religious themes. His works in these years led Islamic devotional songs into the mainstream of Bengali folk music, exploring the Islamic practices of namaz (prayer), roza (fasting), hajj (pilgrimage) and zakat (charity). This was regarded by his contemporaries as a significant achievement as Bengali Muslims had been strongly averse to devotional music. Nazrul's creativity diversified as he explored Hindu devotional music by composing Shama Sangeet, bhajans and kirtans, often merging Islamic and Hindu values. Nazrul's poetry and songs explored the philosophy of Islam and Hinduism.

Let people of all countries and all times come together. At one great union of humanity. Let them listen to the flute music of one great unity. Should a single person be hurt, all hearts should feel it equally. If one person is insulted; it is a shame to all mankind, an insult to all! Today is the grand uprising of the agony of universal man.

The badnaa, a water jug typical in usage by Bengali Muslims for ablutions (wazu) and bath (ghusl) and the gaaru a water pot typical in usage by Bengali Hindus, meet and embrace each other under the peace of the new pact (between the rioting Hindus and Muslims in Bengal during the British Raj on certain politico-religious differences and disputes that had preceded the said pact). There is no knife in the hand of the Muslim and also the Hindu does not wield the bamboo any more! Bodna gaaru te kolakuli korey! Nobo pact er aashnaai! Musholmaaner haatey naai chhuri! Hindur haatey baansh naai!

Nazrul's poetry imbibed the passion and creativity of Shakti, which is identified as the Brahman, the personification of primordial energy. He wrote and composed many bhajans, shyamasangeet, agamanis and kirtans. He also composed large number of songs on invocation to Lord Shiva, Goddesses Lakshmi and Saraswati and on the theme of love of Radha and Krishna.

Nazrul assailed fanaticism in religion, denouncing it as evil and inherently irreligious. He devoted many works to expound upon the principle of human equality, exploring the Qur'an and the life of Islam's prophet Muhammad. Nazrul has been compared to William Butler Yeats for being the first Muslim poet to create imagery and symbolism of Muslim historical figures such as Qasim, Ali, Umar, Kamal Pasha, Anwar Pasha and Muhammad. His vigorous assault on extremism and mistreatment of women provoked condemnation from Muslim and Hindu fundamentalists.

In 1920, Nazrul expressed his vision of religious harmony in an editorial in Joog Bani,

“Come brother Hindu! Come Musalman! Come Buddhist! Come Christian! Let us transcend all barriers, let us foresake forever all smallness, all lies, all selfishness and let us call brothers as brothers. We shall quarrel no more”.

In another article entitled Hindu Mussalman published in Ganabani on September 2, 192 he wrote -

‘’I can tolerate Hinduism and Muslims but I cannot tolerate the Tikism (Tiki is a tuft of never cut hair kept on the head by certain Hindus to maintain personal Holiness) and beardism. Tiki is not Hinduism. It may be the sign of the pundit. Similarly beard is not Islam, it may be the sign of the mollah. All the hair-pulling have originated from those two tufts of hair. Todays fighting is also between the Pundit and the Mollah: It is not between the Hindus and the Muslims. No prophet has said, ‘’I have come for Hindus I have come for Muslims I have come for Christians.” They have said, “I have come for the humanity for everyone, like light’’. But the devotees of Krishna says, “Krishna is for Hindus”. The followers of Muhammad (Sm) says, “Muhammad (Sm) is for the Muslims”. The Disciple of Christ is for Christian”. Krishna-Muhammad-Christ have become national property. This property is the root of all trouble. Men do not quarrel for light but they quarrel over cattle.”

Nazrul was an exponent of humanism. Although a Muslim, he named his sons with both Hindu and Muslim names: Krishna Mohammad, Arindam Khaled(bulbul), Kazi Sabyasachi and Kazi Aniruddha.

Later life and illness

Nazrul, in the 1930s

In 1933, Nazrul published a collection of essays titled "Modern World Literature", in which he analyses different styles and themes of literature. Between 1928 and 1935 he published 10 volumes containing 800 songs of which more than 600 were based on classical ragas. Almost 100 were folk tunes after kirtans and some 30 were patriotic songs. From the time of his return to Kolkata until he fell ill in 1941, Nazrul composed more than 2,600 songs, many of which have been lost. His songs based on baul, jhumur, Santhali folksongs, jhanpan or the folk songs of snake charmers, bhatiali and bhaoaia consist of tunes of folk-songs on the one hand and a refined lyric with poetic beauty on the other. Nazrul also wrote and published poems for children.

Nazrul's success soon brought him into Indian theatre and the then-nascent film industry. The first picture for which he worked was based on Girish Chandra Ghosh's story "Bhakta Dhruva" in 1934. Nazrul acted in the role of Narada and directed the film. He also composed songs for it, directed the music and served as a playback singer. The film "Vidyapati" ("Master of Knowledge") was produced based on his recorded play in 1936, and Nazrul served as the music director for the film adaptation of Tagore's novel Gora. Nazrul wrote songs and directed music for Sachin Sengupta's bioepic play "Siraj-ud-Daula". In 1939, Nazrul began working for Calcutta Radio, supervising the production and broadcasting of the station's musical programmes. He produced critical and analytic documentaries on music, such as "Haramoni" and "Navaraga-malika". Nazrul also wrote a large variety of songs inspired by the raga Bhairav. Nazrul sought to preserve his artistic integrity by condemning the adaptation of his songs to music composed by others and insisting on the use of tunes he composed himself.

Nazrul's wife Pramila Devi fell seriously ill in 1939 and was paralysed from waist down. To provide for his wife's medical treatment, he resorted to mortgaging the royalties of his gramophone records and literary works for 400 rupees. He returned to journalism in 1940 by working as chief editor for the daily newspaper "Nabayug" ("New Age"), founded by the eminent Bengali politician A. K. Fazlul Huq.

Nazrul also was shaken by the death of Rabindranath Tagore on August 8, 1941. He spontaneously composed two poems in Tagore's memory, one of which, "Rabihara" (loss of Rabi or without Rabi) was broadcast on the All India Radio. Within months, Nazrul himself fell seriously ill and gradually began losing his power of speech. His behaviour became erratic, and spending recklessly, he fell into financial difficulties. In spite of her own illness, his wife constantly cared for her husband. However, Nazrul's health seriously deteriorated and he grew increasingly depressed. He underwent medical treatment under homeopathy as well as Ayurveda, but little progress was achieved before mental dysfunction intensified and he was admitted to a mental asylum in 1942. Spending four months there without making progress, Nazrul and his family began living a silent life in India. In 1952, he was transferred to a mental hospital in Ranchi. With the efforts of a large group of admirers who called themselves the "Nazrul Treatment Society" as well as prominent supporters such as the Indian politician Syama Prasad Mookerjee, the treatment society sent Nazrul and Promila to London, then to Vienna for treatment. Examining doctors said he had received poor care, and Dr. Hans Hoff, a leading neurosurgeon in Vienna, diagnosed that Nazrul was suffering from Pick's disease. His condition judged to be incurable, Nazrul returned to Calcutta on 15 December 1953. On June 30, 1962 his wife Pramila died and Nazrul remained in intensive medical care. In 1972, the newly independent nation of Bangladesh obtained permission from the Government of India to bring Nazrul to live in Dhaka and accorded him honorary citizenship. Despite receiving treatment and attention, Nazrul's physical and mental health did not improve. In 1974, his youngest son, Kazi Aniruddha, an eminent guitarist died, and Nazrul soon succumbed to his long-standing ailments on August 29, 1976. In accordance with a wish he had expressed in one of his poems, he was buried beside a mosque on the campus of the University of Dhaka. Tens of thousands of people attended his funeral; Bangladesh observed two days of national mourning and the Indian Parliament observed a minute of silence in his honour.

Criticism and legacy

Nazrul's tomb near the Dhaka University campus mosque

Nazrul's poetry is characterised by an abundant use of rhetorical devices, which he employed to convey conviction and sensuousness. He often wrote without care for organisation or polish. His works have often been criticized for egotism, but his admirers counter that they carry more a sense of self-confidence than ego. They cite his ability to defy God yet maintain an inner, humble devotion to Him. Nazrul's poetry is regarded as rugged but unique in comparison to Tagore's sophisticated style. Nazrul's use of Persian vocabulary was controversial but it widened the scope of his work. Nazrul's works for children have won acclaim for his use of rich language, imagination, enthusiasm and an ability to fascinate young readers.

Nazrul is regarded for his secularism. He was the first person to cite of Christians of Bengal in his novel Mrityukhudha. He was also the first user of folk terms in Bengali literature. He first printed the Sickle and Hammer in any Indian magazine. Nazrul pioneered new styles and expressed radical ideas and emotions in a large body of work. Scholars credit him for spearheading a cultural renaissance in Muslim-majority Bengal, "liberating" poetry and literature in Bengali from its medieval mould. Nazrul was awarded the Jagattarini Gold Medal in 1945 — the highest honour for work in Bengali literature by the University of Calcutta — and awarded the Padma Bhushan, one of India's highest civilian honours in 1960. The Government of Bangladesh conferred upon him the status of being the "national poet". He was awarded the Ekushey Padak by the Government of Bangladesh. He was awarded Honorary D.Litt. by the University of Dhaka . Many centres of learning and culture in India and Bangladesh have been founded and dedicated to his memory. The Nazrul Endowment is one of several scholarly institutions established to preserve and expound upon his thoughts and philosophy, as well as the preservation and analysis of the large and diverse collection of his works. The Bangladesh Nazrul sena is a large public organization working for the education of children throughout the country.

Sources: Wikipedia

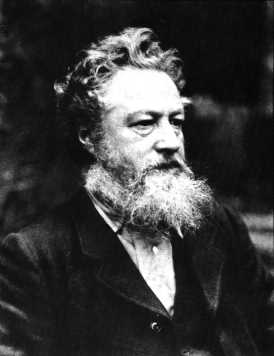

William Morris biography :

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was formed by group of men who did not approve of the way decorative arts, and architecture were being mass produced industrially. Among them was poet British poet, William Morris.

William Morris was born on 24 March 1834 at the village of Walthamstow. Morris came from a well-to-do family and read at Marborough and Exeter College, Oxford. He met his wife, Jane Burden, as well as some of the other members of the brotherhood at Oxford.

Morris started writing poetry while he was at Oxford, and in 1858, The Defence of Guenevere and Other Poems, a book of poetry, was published. He continued to compose poems even though their architectural business (Morris & Company) thrived. Some of his works include The Life & Death of Jason (1867), The Earthly Paradise (1868), and Volksunga Saga (1870).

In 1883, Morris became a socialist. As a member of the Social Democratic Federation, he became a regular contributor to Justice, the SDF’s journal. He left the SDF in 1884, presumably because he and the party leader, H. H. Hyndman, didn’t see eye to eye with the way the party was being run. He formed the Socialist League, together with three other individuals, and contributed regularly to the new party’s journal.

Morris became an active political writer and some of his works include Chants for Socialists (1883), The Pilgrims of Hope (1885), and the booke News from Nowhere (1889). He also composed Death Song, in memory of his friend, Alfred Linnel, who was injured during one of the many socialist political demonstrations in 1887.

Despite being ill with kidney disease, Morris continued to write and give speeches. In his final years, Morris penned Socialism, Its Growth and Outcome (1893), Manifesto of English Socialists (1893), and The Wood Beyond the World (1894).

William Morris passed away on 03 October 1896. His last work was Well at the World’s End (1896). Morris is buried in the village churchyard of Kelmscott.

Source:

William Morris Biography in details

William Shakespeare biography :

- NAME:

William Shakespeare

- OCCUPATION:

- BIRTH DATE:

c. April 23, 1564

- DEATH DATE:

April 23, 1616

- EDUCATION:

King's New School

- PLACE OF BIRTH:

Stratford-upon-Avon, United Kingdom

- PLACE OF DEATH:

Stratford-upon-Avon, United Kingdom

- NICKNAME:

Bard of Avon

- NICKNAME:

Swan of Avon

- AKA:

Shakspere

- AKA:

Will Shakespeare

- NICKNAME:

The Bard

The Bard of Avon was reputed to have been born on 23 April 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon. There are no records of his birth, only that of a baptism on 26 April 1564. His parents were John Shakespeare and Mary Arden. Very little is known about Shakespeare’s youth. Even Shakespearean scholars cannot determine which academic institution he attended in his youth. They, however, believe that, based on young Shakespeare’s knowledge of Latin and Classical Greek, he most probably attended free grammar school in Stratford. William Shakespeare never had formal university schooling. In 28 November 1582, William married a pregnant Anne Hathaway who was 8 years his senior. They had three children: Susanna, and twins Hamnet and Judith. It is unfortunate that Hamnet did not live to see adulthood, he died at age 11. It is not known when Shakespeare arrived in London, but the scholars surmise it to be around 1588. He must have shown much promise as, even during the early stages of his career; he received many an attack on his works. These, however, did not faze the playwright as he continued to write and act in plays such as Lord Chamberlain’s Men. William Shakespeare is probably, compared to his contemporaries, the most successful playwright during his time. He published and sold several of his works, and his company can be considered as the most successful group in London. Shakespeare retired in Stratford in 1611. Just as his birth was full of mystery, so was his death. William Shakespeare supposedly passed away on his birthday, 23 April 1616.

Seven years after his death, John Heminges and Henry Condell, two of his companions in Lord Chamberlain’s Men, published The First Folio, a compilation of previously unpublished works. His Sonnets were first seen through this book.

Details biography of W.Shakespear

Source:

Source:  Shakespear Wikipedia

Shakespear Wikipedia Of Love: A Sonnet

by Robert Herrick

How Love came in, I do not know,

Whether by th'eye, or ear, or no;

Or whether with the soul it came,

At first, infused with the same;

Whether in part 'tis here or there,

Or, like the soul, whole every where.

This troubles me; but I as well

As any other, this can tell;

That when from hence she does depart,

The outlet then is from the heart.

Love Dislikes Nothing

by Robert Herrick

Whatsoever thing I see,

Rich or poor although it be,

. . . 'Tis a mistress unto me.

Be my girl or fair or brown,

Does she smile, or does she frown;

Still I write a sweet-heart down.

Be she rough, or smooth of skin;

When I touch, I then begin

For to let affection in.

Be she bald, or does she wear

Locks incurl'd of other hair;

I shall find enchantment there.

Be she whole, or be she rent,

So my fancy be content,

She's to me most excellent.

Be she fat, or be she lean;

Be she sluttish, be she clean;

I'm a man for every scene.

....................................... ....................................

Alfred Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson, FRS was Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom during much of Queen Victoria's reign and remains one of the most popular poets in the English language.

Tennyson excelled at penning short lyrics, such as "In the Valley of Cauteretz", "Break, Break, Break", "The Charge of the Light Brigade", "Tears, Idle Tears" and "Crossing the Bar". Much of his verse was based on classical mythological themes, such as Ulysses, although In Memoriam A.H.H. was written to commemorate his best friend Arthur Hallam, a fellow poet and fellow student at Trinity College, Cambridge, who was engaged to Tennyson's sister, but died from a brain haemorrhage before they could marry. Tennyson also wrote some notable blank verse including Idylls of the King, "Ulysses," and "Tithonus." During his career, Tennyson attempted drama, but his plays enjoyed little success.

A number of phrases from Tennyson's work have become commonplaces of the English language, including "Nature, red in tooth and claw", "'Tis better to have loved and lost / Than never to have loved at all", "Theirs not to reason why, / Theirs but to do and die", "My strength is as the strength of ten, / Because my heart is pure", "Knowledge comes, but Wisdom lingers", and "The old order changeth, yielding place to new". He is the ninth most frequently quoted writer in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations.

Early life

Tennyson was born in Somersby, Lincolnshire, a rector's son and fourth of 12 children. He derived from a middle-class line of Tennysons, but also had noble and royal ancestry.

His father, George Clayton Tennyson (1778–1831), was rector of Somersby (1807–1831), also rector of Benniworth and Bag Enderby, and vicar of Grimsby (1815). The rector was the elder of two sons, but was disinherited at an early age by his father, the landowner George Tennyson (1750–1835) (owner of Bayons Manor and Usselby Hall), in favour of his younger brother Charles, who later took the name Charles Tennyson d'Eyncourt. Rev. George Clayton Tennyson raised a large family and "was a man of superior abilities and varied attainments, who tried his hand with fair success in architecture, painting, music, and poetry. He was comfortably well off for a country clergyman and his shrewd money management enabled the family to spend summers at Mablethorpe and Skegness, on the eastern coast of England." Alfred Tennyson's mother, Elizabeth Fytche (1781–1865), was the daughter of Stephen Fytche (1734–1799), vicar of St. James Church, Louth (1764) and rector of Withcall (1780), a small village between Horncastle and Louth. Tennyson's father "carefully attended to the education and training of his children."

Tennyson and two of his elder brothers were writing poetry in their teens, and a collection of poems by all three were published locally when Alfred was only 17. One of those brothers, Charles Tennyson Turner later married Louisa Sellwood, the younger sister of Alfred's future wife; the other was Frederick Tennyson. Another of Tennyson's brothers, Edward Tennyson, was institutionalised at a private asylum, where he died.

Education and first publication

Tennyson was first a student of Louth Grammar School for four years (1816–1820) and then attended Scaitcliffe School, Englefield Green and King Edward VI Grammar School, Louth. He entered Trinity College, Cambridge in 1827,[4] where he joined a secret society called the Cambridge Apostles. At Cambridge Tennyson met Arthur Henry Hallam, who became his closest friend. His first publication was a collection of "his boyish rhymes and those of his elder brother Charles" entitled Poems by Two Brothers published in 1827.

In 1829 he was awarded the Chancellor's Gold Medal at Cambridge for one of his first pieces, "Timbuctoo." Reportedly, "it was thought to be no slight honour for a young man of twenty to win the chancellor's gold medal."He published his first solo collection of poems, Poems Chiefly Lyrical in 1830. "Claribel" and "Mariana", which later took their place among Tennyson's most celebrated poems, were included in this volume. Although decried by some critics as overly sentimental, his verse soon proved popular and brought Tennyson to the attention of well-known writers of the day, including Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Return to Lincolnshire and second publication

In the spring of 1831 Tennyson's father died, requiring him to leave Cambridge before taking his degree. He returned to the rectory, where he was permitted to live for another six years, and shared responsibility for his widowed mother and the family. Arthur Hallam came to stay with his family during the summer and became engaged to Tennyson's sister, Emilia Tennyson.

In 1833, Tennyson published his second book of poetry, which included his well-known poem, The Lady of Shalott. The volume met heavy criticism, which so discouraged Tennyson that he did not publish again for 10 years, although he continued to write. That same year, Hallam died suddenly and unexpectedly after suffering a cerebral haemorrhage while on vacation in Vienna. Hallam's sudden and unexpected death in 1833 had a profound impact on Tennyson, and inspired several masterpieces, including "In the Valley of Cauteretz" and In Memoriam A.H.H., a long poem detailing the 'Way of the Soul'.

Tennyson and his family were allowed to stay in the rectory for some time, but later moved to High Beach, Essex in 1837. An unwise investment in an ecclesiastical wood-carving enterprise soon led to the loss of much of the family fortune. Tennyson then moved to London, and lived for a time at Chapel House, Twickenham.

Third publication

In 1842, while living modestly in London, Tennyson published two volumes of Poems, of which the first included works already published and the second was made up almost entirely of new poems. They met with immediate success. Poems from this collection, such as Locksley Hall, "Tithonus", and "Ulysses" have met enduring fame. The Princess: A Medley, a satire on women's education, which came out in 1847, was also popular for its lyrics. W. S. Gilbert later adapted and parodied the piece twice: in The Princess (1870) and in Princess Ida (1884).

It was in 1850 that Tennyson reached the pinnacle of his career, finally publishing his masterpiece, In Memoriam A.H.H., dedicated to Hallam. Later the same year he was appointed Poet Laureate, succeedingWilliam Wordsworth . In the same year (on 13 June), Tennyson married Emily Sellwood, whom he had known since childhood, in the village of Shiplake. They had two sons, Hallam Tennyson (b. 11 August 1852) – named after his friend – and Lionel (b. 16 March 1854).

Poet Laureate

AfterWordsworth's death in 1850, and Samuel Rogers' refusal, Tennyson was appointed to the position of Poet Laureate, which he held until his own death in 1892, by far the longest tenure of any laureate before or since. He fulfilled the requirements of this position by turning out appropriate but often uninspired verse, such as a poem of greeting to Alexandra of Denmark when she arrived in Britain to marry the future King Edward VII. In 1855, Tennyson produced one of his best known works, "The Charge of the Light Brigade", a dramatic tribute to the British cavalrymen involved in an ill-advised charge on 25 October 1854, during the Crimean War. Other esteemed works written in the post of Poet Laureate include Ode on the Death of the Duke of Wellington and Ode Sung at the Opening of the International Exhibition.

Queen Victoria was an ardent admirer of Tennyson's work, and in 1884 created him Baron Tennyson, of Aldworth in the County of Sussex and of Freshwater in the Isle of Wight. Tennyson initially declined a baronetcy in 1865 and 1868 (when tendered by Disraeli), finally accepting a peerage in 1883 at Gladstone's earnest solicitation. He took his seat in the House of Lords on 11 March 1884.

Tennyson also wrote a substantial quantity of non-official political verse, from the bellicose "Form, Riflemen, Form", on the French crisis of 1859, to "Steersman, be not precipitate in thine act/of steering", deploring Gladstone's Home Rule Bill.